The Great Galveston Storm

The Great Galveston Storm

The Great Galveston Storm

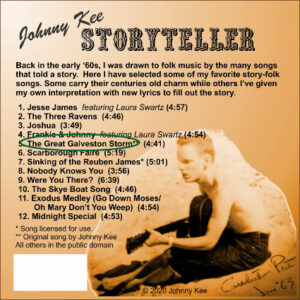

When I was singing with the Bayou Brothers back in Milwaukee in ’62 and ’63, we were all big fans of The Chad Mitchell Trio and did a number of their songs. I first became aware of the “Galveston Storm of 1900” from their song Mighty Day on their ’61 Mighty Day on Campus album. I don’t remember if we did that song as the trio, but I continued to sing and play it solo ever since those days. But back in 2010, I did some deeper research into the event and decided to retell the story from a different viewpoint. The Mitchell Trio version captured the power of the storm, but it left out so much of what made it important and why we need to remember it today.

In 1900, Galveston, Texas was an important port city. It was hard (and expensive) to move goods overland to the booming state of Texas. So goods were moved down the Mississippi River and its tributaries to the port in New Orleans. From there, they were moved by ship along the Gulf Coast down to Galveston. Galveston was situated on a long and slim island a short distance from the mainland, so that the landward side created a well protected port with a deep water channel. Many Americans who settled in Texas arrived through the port at Galveston. By 1900, a railway trestle had been built to move people and goods from the port to the mainland and on to Houston, Beaumont, and other cities. Just as important was Galveston as the port for Texas’ goods (mostly cotton and wheat) being exported to New Orleans and other ports on the Gulf Coast and even to Europe. All this commerce made Galveston a major financial center. It was also a favorite vacation location for people wanting to escape to the Gulf in both summer and winter. Galveston was the first city in the state with electricity, gas lights, and telephones. In 1900, Galveston was a significant and important city.

But back in 1900, although hurricanes were much the same as they are today, we didn’t name them, we didn’t have the system to categorize them, and we were half a century away from being able to track them. The Galveston Daily News of Tuesday, September 4th reported that a tropical disturbance was “moving westward over western Cuba” and was expected to turn north with high winds over the eastern Gulf and Florida coast. The storm strengthened some and moved northward passing near Key West and disappeared into the Gulf.

Four days later, on the morning of Saturday, September 8th, the sea surge from the Gulf created “another overflow,” not all that unusual, particularly at high tide, with water flowing in over some of the streets and into people’s yards. But Isaac Cline, the local forecast official under the U.S. Weather Bureau, thought it was unusually high and determined that likely a tropical cyclone was headed toward the island. Ship to shore radio wouldn’t be invented until 1905, so there was no way to know for sure what was coming. The usual indicators of a storm, “brick-dust” sky, barometer, or wind speed, weren’t there. But the winds from the north, blowing against the surge, were troubling to Cline with the waters rising. Rain poured by midmorning and Cline and his brother went along the coast trying to move people inland to slightly higher ground. But the highest elevation on the island was just under nine feet above sea level. By 3PM, the telegraph and all phone lines were down. Most people were of the mind that they had survived storms before and they would be safe in their homes. Saturday was a workday, and many continued to labor away at their jobs.

The last train left Galveston around 9AM for Houston. The return train from Houston carrying passengers ran late and arrived around 1PM. When the train tried to return, rising waters made it impossible and passengers and crew took refuge at the lighthouse.

The storm surge reached up to 12 feet. Remember the high point on the island was only under 9 feet. Somewhere between 6,000 and 12,000 people died; most official reports put the number at around 8,000. The destruction was unbelievable, and bodies were dug up for weeks. People couldn’t be buried because the water table was so high. Dumping the bodies from barges into the Gulf miles offshore was stopped when bodies started washing back up on shore. In the end, piled bodies were just burned in huge funeral pyres. This storm was the deadliest natural disaster in American history. Over 7000 buildings were destroyed and about 10,000 people were left homeless (out of a population of 38,000). Galveston was rebuilt, but never regained its prominence.

On a 2017 trip to Texas, Claire and I spent a couple days in Galveston. Coincidently, I was able to shoot video of a storm coming in from the gulf. This one was just a run-of-the-mill thunderstorm of no real consequence, but it was eerie looking out and imagining what it looked like on September 8, 1900. I have since used some of that video in a music video for this song, which you can find on my Videos webpage.

By the way, the storm sounds at the beginning of this song were recorded here in Melbourne during one of our afternoon thunderstorms.

Some photos of the aftermath in Galveston (click on an image to see a larger version)…

Listen to a 1 minute preview of this track here: